(RxWiki News) Endometrial cancer is less common in Asian countries than in Western countries. A new study has found these lower rates don't seem to result from a specific food that Asian women eat.

Endometrial cancer is cancer of the lining of the uterus, or womb.

This new study found that endometrial cancer was just as common among Japanese women who ate a lot of food with soy as it was among those who ate less food with soy.

"Talk to a nutritionist about a diet to reduce cancer risk."

Sanjeev Budhathoki, a researcher in epidemiology at the National Cancer Center in Tokyo, Japan, led this study.

The researchers knew that Japanese women had lower rates of endometrial cancer than Western women. These researchers thought the high-soy diet that Japanese women consumed might be protective against endometrial cancer. They set out to see if this was true.

Between 1990 and 1993, 49,121 women, aged 45 to 74, from the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study filled out detailed questionnaires about their lifestyle, medical history and diet. They were specifically asked about their consumption of eight soy foods, including miso soup, tofu and soy milk.

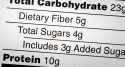

Median intake of soy foods ranged from 38.9 grams per day to 129.6 grams per day.

One of the main nutrients in soy is isoflavone, so the researchers also estimated the women's isoflavone intake. Their isoflavone intake ranged from 17.7 milligrams (mg) per day to 63.2 mg per day.

The women were divided into three groups based on their intake of soy.

Five years later, the women filled out similar questionnaires about their lifestyle and food intake.

The women were followed until the end of 2009. In that time, 112 of the women were newly identified as having endometrial cancer.

Those women who were among the highest consumers of soy or isoflavones were as likely to develop endrometrial cancer as women who were in the group that ate the least soy or isoflavones.

Deborah Gordon, MD, who has an integrative medical practice in Ashland, Oregon, did not find this study's findings to be surprise.

"The study itself was limited primarily because it was a single glimpse of the data, a mere five years out from baseline for a condition that is not a common problem in Japan," Dr. Gordon told dailyRx News.

“I suspect that the role of food-based isoflavones (essentially a hormonal intervention) will always need to be individualized to predict its effect. Relying on our knowledge of physiology, for instance, might lead me to offer isoflavones or individualized hormonal therapy to a woman at high risk for endometrial cancer," she said.

"The nature of the soy preparation makes a tremendous difference, as does the health of the woman," Dr. Gordon said. "Generalizing specific nutrient effects to a society at large rarely works, but an understanding of physiology allows a physician to discuss likely mechanisms with patients, who will then decide on the program most personally suitable."

Dr. Gordon said she wonders if the soy was organic or largely genetically modified. “Could genetic modification techniques or application of the GMO-encouraged pesticide glyphosate affect expected nutritional outcomes?” she asked.

The study's authors concluded that their research found no evidence to support the hypothesis that higher consumption of soy food and isoflavones was linked to a reduced endometrial cancer risk in Japanese women.

They suggested that more studies are needed. “Future studies with a greater number of cases and more precise assessment of exposure variables” are required to verify these findings, they wrote.

This study appeared online June 18 in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.