(RxWiki News) Zelboraf (vemurafenib) was hailed as a huge breakthrough in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, the most lethal form of skin cancer. Now, serious side effects are popping up.

Less than six months after its U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approval, some patients taking the drug Zelboraf for metastastic melanoma are developing secondary skin cancers.

Researchers have come to understand why this is happening and have devised a strategy to prevent this side effect without derailing the drug's primary mission to treat melanoma that has spread.

"Report any side effects to your doctor or pharmacist."

Researchers at the University of California - Los Angeles (UCLA) Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have been working with scientists from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, and the developer and manufacturers of Zelboraf - Roche and Plexxikon.

The team has been trying to understand why the drug is extremely effective in treating melanoma, but also results in skin squamous cell carcinomas in some patients.

According to Antoni Ribas, M.D., co-senior author of the paper and a professor of hematology/oncology at UCLA, explained in a news release regarding these findings, “The side effect in this case is caused by how the drug works in a different cellular setting. In one case it inhibits cancer growth, and in another it makes the malignant cells grow faster," he said.

Zelboraf works by blocking the corrupted BRAF protein in melanoma cells. But this action activates another cellular mechanism that ultimately speeds the development of secondary skin cancers.

About half of the people with melanoma have the BRAF mutation that responds to Zelboraf. About a quarter of these patients taking the drug develop secondary non-life-threatening skin cancers that can be surgically removed.

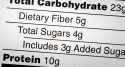

Patients did not discontinue the twice daily oral Zelboraf regimen due to these side effects.

Dr. Ribas and colleagues discovered that the drug was stimulating the growth of skin cells with a mutation of the RAS protein. These cells eventually become squamous cell cancers.

Researchers found this by analyzing the molecules involved in the mutations in the squamous cell lesions of patients treated with the Zelboraf. Dr. Ribas reports that of the 21 tumor samples analyzed, 13 had the RAS mutations. In a second set of 14 samples, eight had these RAS rearrangements.

“This RAS mutation is likely caused by prior skin damage from sun exposure, and what vemurafenib does is accelerate the appearance of these skin squamous cell cancers, as opposed to being the cause of the mutation that starts these cancers,” Dr. Ribas said.

Co-senior author Professor Richard Marais, from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, says another drug can be used to block the cellular activity that leads to these secondary cancers.

“By understanding the mechanism by which these squamous cell cancers develop, we have been able to devise a strategy to prevent the second tumors without blocking the beneficial effects of the BRAF drugs,” Marais said.

Research is currently being conducted to test both drugs in patients who have metastatic melanoma.

Findings from this 18-month study appear in the January 19, 2012 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study was supported by Roche, Plexxikon, the Seaver Institute, the Louise Belley and Richard Schnarr Fund, the Fred L. Hartley Family Foundation, the Wesley Coyle Memorial Fund, the Ruby Family Foundation, the Albert Stroberg and Betsy Patterson Fund, the Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation and the Caltech-UCLA Joint Center for Translational Medicine.